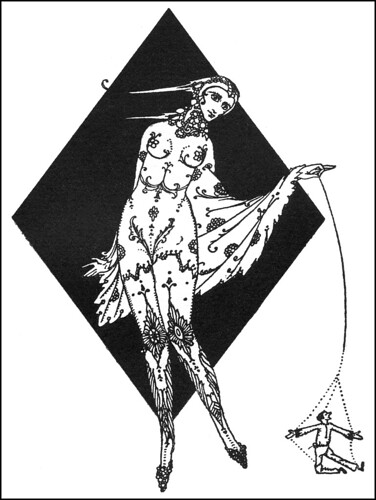

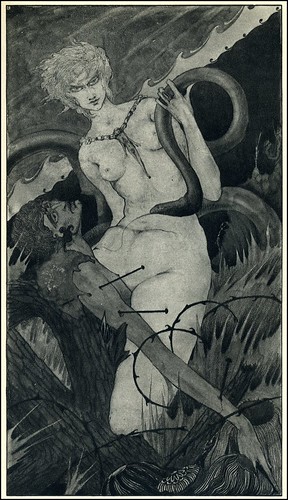

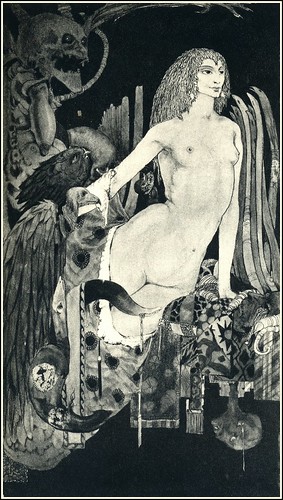

Even if you've never read Swinburne (guilty) – or hope to never read him – you'll enjoy this Lions of Literature column from Gilbert Alter-Gilbert, which features Harry Clarke's fantastic but little-seen illustrations (courtesy of Golden Age Comic Book Stories). Visit the Swinburne Project to sample the poet's work.

2009 marks the centenary of Swinburne's death in (April) 1909. This fact allowed us to rationalize the extra length of a normally brief column.

by Gilbert Alter-Gilbert

If ever there was such a being as a "born poet," that being was Algernon Charles Swinburne.

He was the poet of natural energies and primal forces. He was a lyrical poet par excellence, whose ethereal melodies are unparalleled in his native tongue, and he was equally adept at majestic laments of fantastic despair, soaring hymns to Nature, existential anthems of uttermost metaphysical desolation, and love songs (albeit thwarted love songs) of unearthly beauty. He was, like his contemporary Baudelaire, whom he was first to appreciate outside of France, a sensory poet, an exultant master of mood, scent, and color, as well as a sorcerer of sound and cadence. He could vary his register at will, with unsurpassed dexterity, achieving effects as delicate as the muffled scream of a butterfly whose wing is snagged by a thorn, or as thunderous as a towering wave crashing on a rocky, storm-lashed shore. He was, moreover, of all the great poets, the Grand Initiate of the Mystery of All-Devouring Time.

According to one unimpeachable authority, "Swinburne was the last nineteenth century British poet to create a major body of work commanded by an idea, dominant in England since the generations of Wordsworth, Coleridge, and Shelley, that the poet was the maker of a new reality and the prophet of a universal truth unknown to common apprehension."

The birth of this messianic poet did indeed occur – in Chester Street, near Grosvenor Place, London, England, April 5, 1837, when a son came to grace the estimable escutcheon of Admiral Swinburne and Lady Jane Ashburnham.

CHILDHOOD

Algernon's was an idyllic childhood divided between ancestral estates at East Dene, Bonchurch, Isle of Wight, Capheaton, Northumberland, and Ashburnham Place, Sussex. Always a sickly child – he was not expected to live more than an hour after birth – he thrived, nevertheless and, though frail, became an avid climber, a stalwart swimmer (in the tradition of Byron and Poe, both outstanding aquatic athletes), and a dashing, devil-may-care equestrian. With absolute abandon, he hurtled into the breakers along the beaches of Wight like a maddened sea-creature delirious to regain its native medium. He never tired of galloping his pony hell-for-leather over the furzy Northumbrian downs. Fearless on horseback, he would dare a prancing steed to any feat, and take bolts and spills in stride. Once, without alerting anyone, he made a dangerous solo climb of Culver Cliff, scaling the sheer, seaside precipice to prove his courage to himself. This reckless streak would manifest in wholly other forms later in life.

Arrangement in Grey and Black, 1871 (popularly known as Whistler's Mother): oil portrait of his maternal parent by American expatriate artist James Abbott McNeill Whistler. Whistler's mother revived Swinburne and nursed him to recovery after he fainted while reciting his poetry in the Whistlers' London home. Swinburne was accident-prone, partly because of an innate excitability, partly because of a probable neuromuscular disorder and, partly, because of a devil-may-care approach to physical recreation.

An exceptionally precocious child, young Algernon was educated by his highly refined mother, by an erudite grandfather in whose far-famed library the boy loved to roam and explore and, intermittently, by private tutors. Swinburne was a polyglot at a tender age and genuinely enjoyed linguistic scholarship. He thrived on the classics, translated Greek and Latin with ease, mastered French and Italian and, as was to continue throughout his life, his facility with language expressed itself in the creation of complex neologisms, such as "polypseudonymuncle," for which improbable vocable he readily supplied a friend the impromptu definition: "a horrible little sewer rat who had been convicted under a hundred aliases." Contemporaries variously described the redoubtable juvenile as "a fascinating, most loveable little fellow," "a very spoilt child," and as something of a holy terror – a "demoniac boy who would go skipping about the room declaiming poetry at the top of his voice." While still a child, Swinburne was presented to Wordsworth and to poet, art connoisseur, and cultural arbiter Samuel Rogers who gave the literary cadet his prophetic benediction, proclaiming "you will be a poet." Swinburne was a single-minded literary prodigy from the first and every inch of him looked the part. He wore his shock of red hair in the Struwwelpeter fashion and, relates historian John Drinkwater, "the boy was simply an astounding freak. Imagine a Lilliputian body, with very sloping shoulders, a neck as slender as a lily-stalk, a giant's head, with a crest of orange-fiery hair 'like some strange bird of paradise,' eyes and lips forever twitching in a kind of spasm, a tiny body that, at the least excitement, shivered like a leaf in a tempest, and a voice that shrilled upward like a piccolo." In one youthful incident, the impetuous and high-strung Swinburne burned one of his manuscripts, following its criticism, but then re-wrote it overnight from memory. "Such," says Drinkwater, "was the strange wild being from whom there was to come a strange wild poetry, that yet was charged with the intensest beauty."

ETON

Always "nervous and slight," Algernon wasn't allowed to read a novel until he attained the age of twelve and, after he was enrolled at Eton, he exhibited a voracious appetite for literature. It was there that he conceived his lifelong passion for Sappho, Shakespeare, and Victor Hugo, and composed the first of his gory tragedies about Mary Queen of Scots. He excelled in Greek and Latin, but left the school under a cloud, officially for "reasons still undisclosed" but ostensibly for "incapacity to respond to discipline." Apparently, having acquired a taste for the caning which was a customary method of corporal chastisement at the venerable boys' academy, Algernon not only failed to respond in the anticipated fashion to its application but, having developed a pleasurable sexual fixation for it, deliberately misbehaved as a means of gratifying his pathological craving for the lash. Thus began his much-publicized masochism which, because of his inability to separate pleasure from pain or, by extension, to disassociate other dualities, not only ultimately came to permeate his most powerful poetry, but came close to destroying him physically and morally. Much later in life, a relative cryptically referred in a memoir to "the persecutions at Eton, when he learned to hate all the boys about him."

OXFORD

After leaving Eton, he was intent on joining the Royal Dragoons, but his father, the admiral, mindful of the lad's physical delicacy, and less-than-robust health, refused his entreaties and would not relent. Instead Algernon was enrolled at Balliol College, Oxford, where he was befriended by the master Benjamin Jowett (noted translator of Plato) who is said to have "discreetly rescued" the poet "from his excesses." Swinburne was so skilled with classical Greek that he sometimes clarified some finer point for the distinguished scholar. At Oxford, Swinburne consciously modeled himself after Shelley. He joined the literary society, Old Mortality, and kicked around with the "revolutionary set" "of advanced taste and opinions" who read texts outside the formal curriculum, disdained religion, and embraced radical republican politics. It was also at Oxford that he first met his longtime friends and comrades "Gabriel" (Dante Gabriel Rossetti), "Topsy" (William Morris), and "Ned" (Edward Burne-Jones), as they were painting the Arthurian frescoes for the Union Debating Hall. (Swinburne's own nickname was "Carrots," no doubt on account of his violently red hair.) Rossetti, Morris, and William Holman Hunt, another painter, comprised the founding triumvirate of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, an alliance of poets and painters whose shared aesthetic, by sparking a fascination for medieval subjects and decorative imagery, inflected much of Swinburne's writing during this period.

At Oxford, Swinburne's gnawing religious skepticism culminated in a violent repudiation of authoritarian institutions and ruling hierarchies, including the church and its officers and he even went so far as to spurn God as yet another tyrannical force established to oppressively govern mankind. Swinburne entertained notions of himself as an honorary Gaul – his adored paternal grandfather had been educated in France, was a friend of Mirabeau and dressed himself in the attire of an ancien regime aristocrat. Swinburne loathed Napoleon and all his heirs and became enraged at the mention of the detested name of Bonaparte. He was threatened with expulsion from Oxford in consequence of his very vocal and undisguised support of an Italian patriot who made an assassination attempt against Napoleon III. When neglect of his studies and the disfavor in which his ideological extremism was held by authorities threatened Swinburne's expulsion, college master Jowett intervened on the fledgling poet's behalf, declaring that he couldn't stand by and watch "Oxford sin twice against poetry." (The expulsion of Shelley being the first occasion.) Complaining of his late hours and "general irregularities," Swinburne's landlady, too, was ready to give him the boot. In any case, a riding accident (on horseback, Swinburne had an insatiable craving for speed) prevented him from taking his final examinations and effectively put paid to his academic career and, in 1859, "erratic in studies and intemperate in habits," he left without taking a degree. "Liberty" became the motto emblazoning Swinburne's banner. As had been from his birth and as was to obtain for the rest of his life, it was his preeminent philosophical impetus and his rallying cry.

PRE-RAPHAELITE BROTHERHOOD

For a year or so, Swinburne sporadically continued to study with tutors. During the Crimean War, he was a volunteer, along with Rossetti and the other PRBs, of The Artists Rifles, a rag-tag, comically unlikely company of Laurel-and-Hardy civilian soldiers forming a detachment of the Home Guard pledged to defend England in case of invasion by Russia. He traveled abroad with his family during this formative period, stayed periodically in Newcastle with his painter friend William Bell Scott, and mixed with intellectual circles, frequenting Lord Houghton's literary breakfasts and Lady Trevelyan's soirees at Wallington Hall. Then, in 1861, he set out for London to establish himself as a literary professional. "Poetry," he declared, "is quite work enough for any one man." At first, he resided in North Crescent, off Oxford Street, where rooms had been arranged for him, along with an allowance from his father. Swinburne, now in his early twenties, savored the attractions and distractions of London to the full. Pre-Raphaelitism was in its heyday, and he fell more fully under the sway of Dante Gabriel Rossetti with whom, beginning in 1862, he came to move from his lodgings in Grafton Street, Fitzroy Square into a house in Cheyne Walk, Chelsea, also shared with Rossetti's sister Christina and, briefly, with the novelist George Meredith. In 1848, poet and painter Dante Gabriel Rossetti, in concert with fellow painters William Holman Hunt and John Everett Millais, had organized the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood as a secret society revolving around a rejection of the materialism of an increasingly industrialized Britain, and as a reaction against what they considered the low standards of British art then prevailing. The Pre-Raphaelites, so named because they "found a happy innocence in the works of Italian painters prior to Raphael," sought refuge, through symbolism and imagery, in a fablelike vision of the Middle Ages. They fancied themselves devotees of "nature and truth," cleaving to the simplicity of a more innocent time, acolytes of a cult of beauty built around a melancholy nostalgia for the code of chivalry and the idyllic epoch of Arthurian romance. Some scholars have linked Swinburne artistically with the Pre-Raphaelite movement and classified him as a card-carrying practitioner. But Swinburne was always his own man and, though sharing an affinity for medieval lore, and a fondness for the period which framed it, he was drawn at least as much to still more archaic models – classical Greek and Latin literature – and was as apt to daydream about Sappho on her glittering Aegean Isle and centaur-and-nymph-filled Arcadian meadows pre-dating the Age of Pericles as about Lancelot and Guinevere. Strictly speaking, the majority of poetry that can be considered Pre-Raphaelite proper is that found in the pages of The Germ, a short-lived literary journal that served as the unofficial organ of the movement during the year of 1850, when Swinburne was still a schoolboy at Eton. Consequently, it is a mistake to lump him with Pre-Raphaelitism's principal players, as he was peripheral to the movement, at best. He and Rossetti, Pre-Raphaelitism's high priest, remained intimate friends and, in a general sense of artistic trail-blazing, comrades-in-arms throughout the 1860s. However, when Swinburne and his sidekick, the transvestite painter Simeon Solomon (who later, much to the discomfort and chagrin of all who knew him, ended up in Oscar-Wilde-like disgrace when he was convicted of homosexual soliciting) ran around Rossetti's Tudor House decked out as Greek pagans in nothing but laurel wreaths and sandals, then slid down the banister naked, Rossetti threw them out. Two years prior, Rossetti's wife, Elizabeth Siddall, had died from an overdose of laudanum. During the period leading up to her death, Swinburne had been her closest companion and was required to testify at the inquest. As a formal unit, Pre-Raphaelitism would not outlive this shock to its chieftain. Haunted Rossetti grew morbidly involutional and became addicted to alcohol and chloral hydrate. Morris continued as something of a spokesman and apologist for Pre-Raphaelite principles and theories and went on to lay the groundwork for the Arts and Crafts movement in architecture and design. Burne-Jones and the other painters attained the heights of artistic acclaim.

TRAUMA, CONTROVERSY, DISSIPATION

During the early 1860s, Swinburne suffered many shocks and losses – besides the death of Elizabeth Siddall, there were several significant deaths in his own family, and he was rejected in love – some say by his cousin Mary Gordon; others say by Jane Faulkner, daughter of Sir John Simon. In any case, this romantic rebuff was a blow from which, in one sense, he never quite completely recovered. He had already spurned the church. Now his pessimistic nihilism set in, and assumed a permanent cast. He had fallen in with a fast company – the scoundrel and all-around shady character Charles Augustus Howell, the exquisite and roué Richard Monckton Milnes (Lord Houghton, one of Tennyson's fellow Apostles), and the anti-Victorian Richard Burton, translator of the Arabian Nights and interpreter of the sexual mores of the Levant. This trio of rogues expertly led him astray and schooled him in the ways of haute dissipation. Milnes introduced him to the writings of de Sade; Burton introduced him to brandy, of which he soon began to assimilate inordinate amounts. Svengali-like Howell, who charmed both Algernon and Gabriel Rossetti (also whose affairs he managed) is described in contemporary accounts as a suave buccaneer who, in an earlier era, would have gone about in seven-league boots, with a sword and a flintlock pistol in his sash, and a plumed hat on his head. Milnes later arranged for Algernon to meet Robert Browning and Matthew Arnold. Though he admired these poets as well as Tennyson and Dickens, none of them much reciprocated. Swinburne and Burton shared a hearty contempt for Oxford University, from which Burton, like Shelley, had been expelled; Swinburne avoiding the same fate only because he quit before expulsion could be effected. Throughout his twenties and thirties, Swinburne was caught in a vicious circle of drunken binges, recuperation, then more binges. More than once, he turned up at Rossetti's doorstep in the wee hours, dead drunk. Burton had often "after their sessions, to tuck the unconscious Swinburne under one arm and carry him out to a cab." Algernon went to Paris and the Pyrenees with his family in 1862, he went again to Paris with Whistler in 1863, and with Milnes in 1864 (during this last trip venturing as far as Italy to meet Landor). His drinking increased during this period and he developed epilepsy. He was known to pass out during the throes of furor poeticus, so carried away did he sometimes get during a recitation. In the summer of 1863, after a fall at the studio of James McNeill Whistler, he was nursed back to health by the artist's mother. Swinburne's refined aestheticism influenced Whistler who, in turn, became one of the two men most associated with the Aesthetic Movement; simultaneously, the Rossettis influenced Swinburne by deepening his interest in Blake and Shelley, about whom he wrote studies in 1868 and 1869 respectively.

In 1864 he joined the Art Club in London and, in 1865, the Cannibal Club.

Around this time, Swinburne enjoyed a brief dalliance with the flamboyant American poetess and circus bareback rider Adah Isaacs Menken, a sort of Lola Montez type notorious for her multiple marriages and steamy liaisons with famous literary men. Celebrated for both her pulchritude and her charm, Menken was internationally famed for the skimpy flesh-toned leotard which clingingly costumed her curvaceous figure during her performances. Once, when she began to converse about literary matters, Swinburne politely cut her short, saying "Darling, a woman who has such beautiful legs need not discuss poetry." In a photograph with her, William Gaunt describes him as "looking meek and dwarfed by her buxom contours." Swinburne idolized Adah and wrote a poem for her but, apparently, was unable to satisfactorily consummate this conventional heterosexual passion; in his finest sadomasochistic fashion he tried to excite her by biting her – alas, to no avail.

In 1868 Swinburne was invited by the Reform League to stand for Parliament.

Like a fugitive from a page of de Sade, Algernon had a weakness for the swish of the whip and was a regular visitor to houses of flagellation, such as the quaintly named Verbena Lodge, a bondage lounge in St. John's Wood, and his health was increasingly compromised both by his worsening algolagnia and the excessive consumption of alcohol. (As with Poe, a capful would send him over the edge.) For thirteen years, from 1866 on, his patronage of gin mills, paddling pits, and other sloughs of iniquity would make his life a putrefying sink. A climbing expedition to Auvergne to scale the Puy de Dome with Richard Burton, and salubrious outings to Cornwall and Scotland with Benjamin Jowett briefly fortified Swinburne's fragile constitution. He visited Paris and Florence and met Manet, Turner, Victor Hugo and Landor, then ninety years old and living in Fiesole in a house secured for him by the Brownings. All the while he was struck by blow after cruel blow: Simeon Solomon was prosecuted, a la Oscar Wilde, for homosexual enticement, death claimed Mazzini, and Rossetti suffered "permanent emotional collapse." He would never see them again.

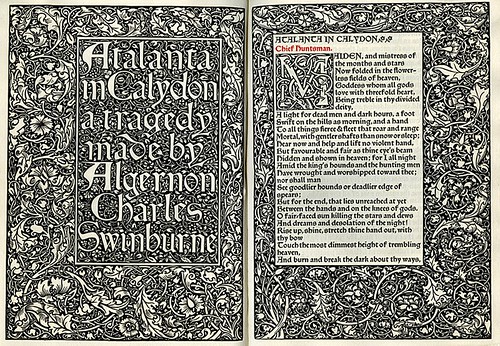

In 1865, Swinburne's drama in verse Atalanta in Calydon made its sensational debut, and instantly put him on the literary map. In the wake of the publication of the first series of Poems and Ballads, which quickly followed in 1866, Swinburne became the subject of a famous denunciatory diatribe by Robert Buchanan called The Fleshly School of Poetry printed in The Contemporary Review. The Saturday Review joined the fray, proclaiming a state of siege against decency and accepted social standards.

Summarizing not the effect, but the inner character of this novel, high-impact poetry, one scholar notes that "in Atalanta in Calydon, Swinburne used his thorough classical knowledge and sympathy with classical Greek literature to turn a Greek myth and tragic form into a fundamentally lyric enactment of a reality in which love, beauty, human consciousness, and the capacity for speech itself are painful ironies in a world governed by accident and doomed by time and death. In the first series of Poems and Ballads, he continued to explore this world and, like Baudelaire, registered a moral disgust at the exhaustions and perversions of mortal flesh pushed to its limits by wishes for a wholeness and health that material existence cannot satisfy. In these poems time itself is running down, the fabric of things is unraveling, and gods as well as men are dead or dying."

Swinburne's Olympian appetite for freedom, coupled with the elegant nastiness of his anti-theist nose-thumbing, incensed strait-laced Victorians. Oppositional elements aligned on every side to revile the concupiscent sympathies and degenerate sensibilities of Swinburne's intoxicating new poetry and, throughout his stormy career, from this ominous onset forward, his work was "vigorously attacked for its 'immorality' and 'feverish carnality,'" while the shrill objections to the "diseased state of mind" whence the poetry derived never entirely died away.

As Atalanta in Calydon and Poems and Ballads had time to take hold, the public became polarized in their defense or disapprobation. Even Swinburne's champion, John Ruskin, who called Atalanta in Calydon and its coruscating choruses "the grandest thing ever done by a youth," qualified his judgment by temperately adding "though he is a demoniac youth." Swinburne's work was "savagely attacked for its sensuality and anti-Christian sentiments, but almost as excessively praised in other quarters for technical facility and infusion of new energy into Victorian poetry." The poet took the public gaze, and began to enjoy at once a vogue that may almost be likened to the vogue of Byron. He exerted a "sudden and imperative attraction" and, "by the close of his thirtieth year, in spite of hostility and detraction, Swinburne had placed himself not only in the highest rank of contemporary poets, but had even established himself as leader of a choir of singers to whom he was at once master and prophet." Oxford undergraduates regarded him as little short of a demi-god and marched through the ancient halls and ivy-clad cloisters chanting Dolores as if it were a revolutionary oath. He reveled in his popular image as an "exultant dervish of the immoral." He was a bit of a show-off and didn't shrink from grand-standing when the opportunity presented itself. He bragged that when his projected Hymn of Man appeared, it would put Shelley's Queen Mab to shame. As Swinburne's lyrical masterpieces percolated into the bloodstream of Victorian consciousness, the poet began to swing away from pagan themes and erotic dreams to songs of the Risorgimento (Songs Before Sunrise), for he had befriended the revolutionary Mazzini and embraced the cause of Italian reunification. Even as he cranked out book after book, shifting in theme and approach (and including, besides important poetry, groundbreaking studies of William Blake, Percy Shelley, and Charlotte Bronte), he embarked on a decade and more of intermittent dissipation. Public perceptions of the poet, whether warped or accurate, couldn't be disentangled from the work and became conflated in the general mind. The fact that Swinburne enjoyed riling smug Victorian society and flaunted his taboo-exploding poetical provocations in its sanctimonious face caused the more conservative of his countrymen to conclude that this poet enamored of lesbians and dominatrices, necrophiliacs and lepers must be a deviate guilty of who-knows-what perverse pleasures and unspeakable indiscretions in his private life. Pungent and pugnacious critics prodded him with their pikestaffs as if he were an execrable monster, a depraved and degenerate dragon to be slain in the interests of the public moral good. Critical attacks were fierce and Swinburne girded himself for battle against a rising tide of animadversion, a literary pugilist publishing pamphlets such as Under the Microscope defending his position as a free-thinking artist.

Public perceptions and critical estimations of Swinburne's persona and poetry have been vociferous and mixed. He has been called virginal, homosexual, bisexual, polysexual perverse, an atheist, a sublimated theist, a radical, a reactionary, a nihilist. Edmund Gosse called him "not quite a human being"; Maupassant called him "supernatural"; Turgenev said "positively anything could be expected from him – he was far from a normal person." Oxford don and all-around cultural cicerone John Ruskin leapt to his feet blurting encomia on first hearing Swinburne's verse. Ejaculating "What divine music!" and "Glorious!," the High Victorian poohbah gushed that Swinburne's lines were marked by a "frenzied rush of rhythm that sweeps the soul before it"; and of the author who created them, "he simply sweeps me away before him as a torrent does a pebble": according to Drinkwater, "these sayings perfectly express the double gift of Swinburne – the strange new tunes of his rhythms and the torrent-sweep of his verse." Alfred, Lord Tennyson called him "a reed through which all things blow into music." Oscar Wilde remarked, "He is so eloquent that whatever he touches becomes unreal." John Drinkwater maintained that experiencing a Swinburne poem is, "as it were, to hang a splendid picture in the gallery of the mind or to fill the soul with the remembrance of a glorious symphony," and that Swinburne's poetry carries us away to "a land enchanted, a land of strange, unearthly blossoms," a "wonder-world" which is the dwelling place of "phantasmal women who are the daughters of sweet dreams." By and large, however, Swinburne's Victorian elders strongly disapproved. A dismissive Browning summarized Swinburne's verse as "a fuzz of words." Crotchety Carlyle referred to it as "the miaulings of a delirious cat." A carping Matthew Arnold, in a less than generous mood, referred to the upstart as a "sort of pseudo-Shelley." Swinburne was caricatured in Punch by novelist / cartoonist George du Maurier as poet Jellaby Postlethwaite while the role of Bunthorne in the Gilbert and Sullivan opera Patience, ultimately based on Oscar Wilde, was originally conceived as a satire of Swinburne. In Mortimer Collins's novel Two Plunges for a Pearl, Swinburne was burlesqued as the character Reginald Swynfen, "a little man built like a grasshopper." The press called him "Mr. Swineborn" and plastered him with pejoratives.

Swinburne courted this notoriety and took a devilish delight in being the cynosure of scandal. Because of what were perceived by the public as his heretical, anti-theist views and gross licentiousness, he was branded an apostate (shades of Percy Shelley) and dubbed the "libidinous laureate of a pack of satyrs." He thrived on the attention and on his ability to cause the British tea kettle to "seethe and rage," as he coyly put it.

"There were of course antecedents for Swinburne's idea of himself as a poet in society. Among the models – he called them 'masters' – of his early poetry were William Blake, Shelley, Victor Hugo, and Walt Whitman, poets who wrote in large literary forms and who wanted to effect philosophical, social, and political change by their words. Until the end of his life he wrote in the familiarly grand forms of Elizabethan as well as classical drama, long narratives, elegies, ceremonial odes, and a kind of long meditative lyric, in the tradition of Wordsworth's Tintern Abbey and Shelley's Mont Blanc, of which On the Cliffs is an exceptionally complex example. At the climax of his powers, he made the new mythologies of Hertha and Hymn of Man, in which he articulated the doctrine that the redemption of an exhausted time would come not from an incursion of the divine but from a fulfillment of the capacities of the human. He wanted to perform the entire office of the romantic poet as prophet. Swinburne's contemporaries often thought him not only extreme, but excessive." [Ed.: we lost the source for this quote.]

Certainly Swinburne gave his fellow Victorians ample grounds for regarding him as an ogre. It is difficult to determine which of his transgressions offered greater offense: the lush sensuality, diseased with debauchery and dripping with decadence; the blasphemous paganism, which "attacked Christianity for its doctrine of death"; the advocacy of Shelley's idea of a religion-free society, borrowed from the French Revolution and its Goddess of Reason; or the depiction of a stern, implacable Nature which marched in concert with the gods Time and Inevitability towards the extinction of all things in a cycle of eternal recurrence. Is it any wonder that when Poems and Ballads appeared in 1866, it sent shock waves through Victorian England? "It was received with a scream of hysterics on the grounds of immorality" and, so startling was its effect, that the publisher canceled the book and it dropped from circulation before being re-issued by another. "God is the supreme sadist in Poems and Ballads," observes John D. Rosenberg. Swinburne, according to Rosenberg, rebelled against and committed "defiance and desecration" of a God who "grinds men in order to feed the mute, melancholy lust of heaven." Swinburne was not only the "poet as impudent sensualist insulting prevailing Victorian mores," he was the poet of Time, poet as prophet of a New Order; poet as harbinger of a philosophical message; poet as metaphysical initiate of life's deepest mysteries.

Swinburne was possessed by an indefinable quality poetically known as the divine afflatus or, as Spanish poet Federico Garcia Lorca called it, the duende – a spirit force that charged his every utterance with maniacal fervor. Max Beerbohm referred to the experience of listening to Swinburne speak as like listening (to borrow the refrain from one of Swinburne's own poems) to the "song of a secret bird." Beerbohm states that ever after Swinburne's days at Oxford, generations of students continued to ape his speech patterns and mannerisms. When Swinburne recited his poetry, so feverish was his delivery and so ardent his excitement that he would bounce to his feet from his seat on a sofa, and back again to a seated position, all the while gesticulating wildly like one possessed. He was chronically fidgety and twitchy, and couldn't keep his hands still. The slight frame of his small body shook convulsively and jerkily as a puppet's when he was animated by some passion. At different times, Swinburne was said to suffer from a nervous tic, fainting spells, trembling "fits," and uncontrolled speech which Beerbohm informs us an attending medical specialist attributed to "an excess of electric vitality." It has been theorized that Swinburne's condition consisted of anything from Tourette's Syndrome to epilepsy.

His masochism apparently found extended expression in hero-worship; he seems to have substituted a sense of abasement before human idols for the traditional equation of supplicant to deity. When he was introduced to the Italian nationalist Mazzini, he kneeled in prostration. He toted a footstool to a banquet in order to pay proper homage to Robert Browning. He was forever writing adulatory tributes to this one and that. He had a great capacity for fanaticism and adoration. He tried to seduce Adah Isaacs Menken by applying childlike love-bites. Unexcited by his clumsiness, she did not respond. Swinburne routinely indulged in a raft of additional gestures of self-humiliation that went well beyond the superior grooming, impeccable manners, and even the most rudimentary and conventional courtesies presupposed of a lordly English gentleman.

He had a perpetually juvenile, even infantile quality. Puckish, implike, he was Peter Pan personified, and had a dependent nature which, when not nourished, led him to quickly disintegrate.

Swinburne carried in the very fiber of his being the anti-industrial creed of the Pre-Raphaelites. Even though he lived well into the early years of the automobile, he studiously avoided machinery. He hated typewriters, read by candlelight and refused to adapt to gas jets let alone electric fixtures, and couldn't work the squirter of a seltzer bottle.

0 comments:

Post a Comment