by Gilbert Alter-Gilbert

(part 2)

THE AESTHETIC MOVEMENT

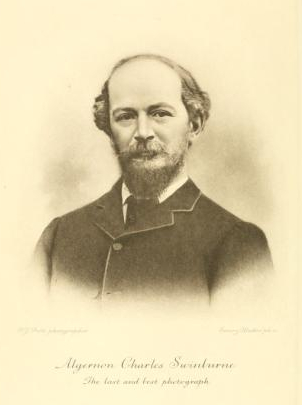

Swinburne, together with Oxford academician and "gospel of beauty" high priest Walter Pater, and American expatriate painter James McNeill Whistler, adopted Théophile Gautier's dictum of "art for art's sake" and codified what came to be known as the Aesthetic Movement in England, which pre-dated but was embraced and championed by Oscar Wilde and remains most famously associated with his name. At the same time, the movement anticipated many concerns of the Symbolists and Decadents and was, along with the vogue for Poe and Baudelaire, a principal pater familias. Bracketed by Pre-Raphaelitism and the Symbolist phase and Art Nouveau, the Aesthetic Movement effectively bridged this period of artistic ferment, finding full flower between 1870 and 1875. Swinburne's "religion of beauty" was a creed shared wholeheartedly by former Pre-Raphaelites and by prominent Aesthetic Movement adherents such as Wilde and Whistler.

Undeserved or not, Swinburne's reputation for vice and license followed him for a decade, from the late 1860s to the late 1870s. It was a reputation he cultivated and did nothing to counteract. His reckless lifestyle continued unabated. William Gaunt imagines the trio of Milnes, Swinburne, and Burton in the social swirl of London's velvet underground during a nocturnal tour: "…at Cremorne in the Hermit's Cave and Fairy Bower amid the polka-dancing mob. One hears the pop of champagne corks and the gurgle of the brandy bottle in some blazing resort near the Haymarket. One sees Swinburne subsiding in the midst of a wreck of glasses, repeatedly comparing himself with Shelley and Dante, asserting that two glasses of green Chartreuse were a perfect antidote to one of yellow or two of yellow to one of green. One sees him and his companions venturing into the slum quarters which were then infernal in their wildness and riot…" These years "furnish innumerable accounts of Swinburne's disgraceful behavior, snatching at bottles 'like a mongoose,' 'belching out blasphemy and bawdry and wasted by drink.'" He had fallen in with a bad crowd. He announced at a party that he wanted to "build seven towers, in each of which to enact one of the seven deadly sins." He and a chum raided the cloak room of a prominent gentlemen's club, gathered up the top hats of the members and crushed them by stomping on them until they were unceremoniously ejected from the premises. Careening around the night spots of the capitol, Swinburne might turn up at a function at Rossetti's in evening clothes or might just as unsurprisingly justify Ruskin's bemused wonder "whether the boy would ever be fully clothed." He had achieved Byronic status, which had been his goal from the outset.

Edmond de Goncourt wrote a novel involving a character based on a composite of Swinburne and Oscar Wilde. Goncourt asserted that Wilde's homosexuality was largely a pose plagiarized from Verlaine and Swinburne. Goncourt, who wrote the introduction to the 1891 French edition of Swinburne's Poems and Ballads, and who was never averse to the raw and the raunchy, cited in his famous Journal a number of juicy and salacious entries concerning Swinburne, beginning with an incident related by Guy de Maupassant which supposedly took place in 1868 on the Normandy coast near Dieppe as Swinburne was visiting the seaside town of Étretat where he shared a cottage with his confrere, the folklorist and translator George Powell. It seems that one morning, while out for a swim, dainty and petite Algernon was swept out to sea by treacherous undercurrents and barely saved from drowning, as legend would have it, by none other than the teen-aged Maupassant who, coincidentally, happened to be vacationing in the area at the same time. After hearing shouts for help, the huskily-built Maupassant dove into the waves, and made his way through the rock arches near the palisaded beach and began to race towards Swinburne as he floundered some two miles offshore. Soon enough, the hapless poet was scooped from the brine by a passing boat, but all who participated in the rescue were feted by the grateful near-victim, most of all the handsome and brawny Maupassant, who was invited to dine with Swinburne and Powell chez eux. (Safely back on shore, Maupassant stated that Swinburne had been "dead drunk" at the time of his nautical misadventure.)

What happened next, according to Goncourt who, as a French naturalist, did not shy from the raw and the raunchy, was a juicy and salacious series of incidents that have been handed down to posterity as fact, however much they may have been embellished by both the gossip-loving popular imagination and by the sensation-hunger of Swinburne himself, who never refuted them.

Home in London, it was clear that Swinburne's life of dissipation did not mean one of dessication. His authorial output was unattenuated though "in these years he sometimes became so ill as a result of the unregulated habits of his life that he had to be taken to his parents house to recuperate." It was evident from the appearance of the second series of Poems and Ballads in 1878 that an "autumnal mood" had descended over Swinburne's verse. It was "a mood not of the residue of energies desperately spent or fearfully thwarted, but rather of the slow encroachment of time, the sea eroding the shore, the night darkening the sea." These poems fulfilled Swinburne's "ambition to be a great poet in the way of his masters. In them Swinburne leaves the desolate landscapes and the quiet tonalities characteristic of late century verse to penetrate again the deep, dense life of things and to find again words, rhythms and forms that will make or manifest realities whose power and meaning none will know until a poet speaks them." Swinburne's "energy was at fever height, the current of his poetry continued unchecked"; his poetry had transited from "the sensual sphere, through the political and ecclesiastical, with the virulent animosity of its detestation of kings and priests" and through the phase of "what has been called his 'pan-anthropism' – his universal worship of the holy spirit of man, the gospel of the 'body electric' and the glory of human nature" to a new plateau of "passages of power and intensity unsurpassed, in which the fecundity of his versification and the force of his melody were unbroken, and his magnificent torrent of words inexhaustible."

Although, by the time he was in his early forties, Swinburne's literary precocity remained unimpaired both in quantity and quality, he was physically fading fast. His boozing had worsened. When he was out on the town, he often had to be assisted to a cab and, when delivered home in the wee, wee hours, dumped on his doorstep, blind drunk. When left to himself, he drank until he blacked out. The squalid cycle of dissipation, collapse, recovery, and fresh dissipation was taking its toll, and his health began to fail. His masochistic indulgences continued undiminished and his deafness deepened. By 1879, periodic "recuperative intervals were too rare to save him" and his "phenomenal energies were at last subdued by alcoholism." Swinburne is a pathetic figure at this point. A plaintive tone informs his letters, a note of sadness, a wistful sorrow tinges his conversation. Pining for his "lost love" and pained by the slanders of others, he finds himself snared by mounting isolation and by the downward spiral of dissolution. Ruing his revels and carousals, and suffering in conscience, he is penitential over the debaucheries from whose consequences he may soon succumb. "Incapable of moderation," Swinburne had become a lush of epic proportions – a prototype of Dylan Thomas and Brendan Behan and all titanic tipplers of British literature to follow. Both Swinburne and his quondam comrade Rossetti were broken men at this point but their mythic stature had been irrevocably cast.

An epileptic algolagniac prostrated by alcoholic dysentery and spiraling towards death, he helplessly awaited his fate…

Enveloped by solitude, swallowed by squalor, eaten alive by sheer physiological deterioration, Swinburne's situation was one of the acutest peril. Realizing the emergency, Swinburne's mother importuned his friend, the poet-solicitor Theodore Watts-Dunton, to intervene before it was too late. A sordid scene ensued when Watts-Dunton entered Swinburne's rooms, and found before him a crippled wretch. The kindly lawyer bundled the wreckage of the greatest nether-poet then living in England, and helped him into the compartment of a waiting coach. The grimness of Swinburne's condition is not to be exaggerated and Watts-Dunton's simple act of gallantry unquestionably saved the bard from certain catastrophe.

By 1879, Swinburne was living in an advanced state of misery and degradation to which Watts-Dunton's wife, in a memoir, macabrely refers as the days of "roses and raptures." He was a broken reed who had reached a point where family, friends, and physician had all but written him off. When Swinburne's attorney, business manager, and literary cohort broke in on him and scooped him up from his rooms in Great James Street, in the center of London, and spirited him off to the outlying district of Putney, first to No. 11 Putney Hill, then down the way to No. 2, The Pines, a house which Watts-Dunton, or "Walter," as he was familiarly known, shared with his sister and servants and, later, with his young, worshipful wife Clara, he removed a creature lost to the world, and installed him in the bosom of comfort and security. Swinburne had been altogether unable to take care of himself. Now he had residence in a country retreat, a salutary haven formed by congenial quarters and the quiet companionship of caring friends. The simple remedial measure of removing him from the pernicious influences which had undermined his health resulted in a miraculous cure, and Swinburne underwent a remarkable and complete restoration.

Shut up at The Pines but for an occasional trip to the coast (under supervision) to satisfy his infatuation with the sea, Swinburne effectively became a scholar-hermit, devoting the last thirty years of his life to assiduous literary activity, and growing into an increasingly respected grand old man of letters under the benign stewardship of Watts-Dunton, who became his de facto guardian. Many of his old friends thought him "imprisoned," but his prodigious productivity during these years proves incontrovertibly the salubrious effect of tranquil surroundings and steady routine on his equilibrium. By successive steps and stages, Watts-Dunton gradually weaned Algernon from an accustomed intake of brandy in ghastly amounts to a few glasses of milder wine and, eventually, to a single tankard of ale per diem. The unusual filial arrangement of this Damon and Pythias of Putney Hill ensured that, "after 1880, Swinburne's life remained without disturbing event, devoted entirely to the pursuit of literature in peace and leisure."

During this picturesque period of retirement at Putney, Swinburne's eccentricities multiplied and intensified. In the course of his daily wanderings through the woodlands surrounding Putney Heath, he would greet his favorite trees and do them obeisance by chivalrously bowing and doffing his hat on parting from each one. He spoke to them familiarly; running from one to the next, repeatedly ejaculating "ah-h-h!" An impish, elfin figure, he flitted through the woods like a nature-sprite, springing and leaping, cavorting and capering, skittering among his arboreal friends, rhapsodizing them with eloquent tributes. One could easily be persuaded that he honored them above mere creatures of flesh and blood. He composed poems during his sylvan rambles, and sang them as he strolled along.

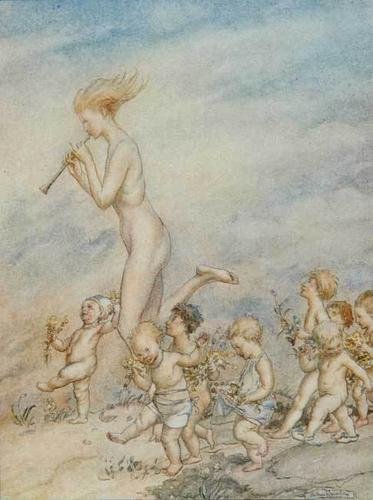

An Edwardian era portrait of Swinburne as a hairy satyr delighting an audience of naked babes (above), which adorns a posthumous collection of his child-poetry reinforces a popular perception that, in his later years, the illustrious bard had become a "babyolater." His volume A Century of Roundels included twenty-four florid poems about infants and toddlers. From among them, Edward Elgar, the English composer, adopted as a libretto the odelet A Baby's Death. (Perhaps this is no stranger than the fixation on juvenile themes peculiar to Eugene Field, James Whitcomb Riley, or other august predecessors of the Hallmark School but, coming from an author once accused of promulgating "peccant" verse which was the product of "the spurious passion of a putrescent imagination" in which "the Bottomless Pit encompasses us on one side and stews and bagnios on the other," it carries more than a little resonance of something odd.) Now, in his upper years, Swinburne routinely spent part of his daily round rejoicing in "beautiful," fresh-faced infants randomly encountered in their nanny-propelled prams while taking the air in Wimbledon Common, and apostrophizing these beaming babies of the neighborhood in reverent paeans and jocund odes. With a touch of the dotard, he goofily fawned over these bubbling bundles of joy, gushing like a grandmother over every dimple, squint, hiccough, and burp. He also amused himself during these years by writing farces and hoaxes, pornography, bawdy limericks, naughty skits, and a lubricious treatise about flogging titled The Whippingham Papers. Some of his efforts remain "unpublished and unprintable." These essays in the racy and risqué were not a passing phase; Algernon the prankish schoolboy had been at them all along. It was an impulse he had never outgrown.

In his library Swinburne kept a bronze statuette of Victor Hugo presented to him by his sculptor friend Lord Ronald Gower. "A lithe, energetic man with wonderful, twinkling eyes" surrounded by thousands of books in his study at The Pines, Swinburne radiated happiness. An impassioned bibliophile, he knew exacting details about, and could rattle off minutiae concerning every one of the thousands of books in his personal collection, and was puzzled and amazed whenever a visitor to his study didn't possess the same erudition in book lore as he. With mathematical precision, he could pinpoint the precise location of any volume on his groaning shelves and, after pulling it down for display from the tottering stacks, would go over it thoroughly with a red and black checkered duster, as he had a horror of handling a dusty book and couldn't bear to touch one unless immaculate. Puttering merrily about his library rapturously muttering oohs and ahs as he flitted from book to book, this was where Swinburne received the occasional visitor.

Contented as he was in his comfortable surroundings, he wasn't always docile as a kitten. As has been mentioned already, the poet felt a scathing hatred for Napoleon Bonaparte; the merest reference to that detested Gallic personage would provoke him to spew niagaras of abusive verbiage. Such outbursts were not confined to execrations of the emperor exiled to Elba; other peeves could trigger furious tirades just as easily. He was the gentlest of gentlemen except when fuming about some literary foe. It may be this was a belated release of steam for all the high-handed and vindictive pontifications hurled at him during the 1860s and 1870s, against which he had never publicly retaliated.

This epicure of books regularly could be found "inarticulately ecstasizing" over one of his favorites or indecisively flipping through another, assessing its virtues or demerits, pronouncing commendation or condemnation. Woe unto the author who did not meet with his approval; such an unfortunate would be flayed alive. Against those he disliked, his tongue lashed viciously. Courteous to a fault with visitors, he was nevertheless roused to petulance when confronted by the merest divergence from strictly regulated daily routine. Punctilious and pedantic, he would fly into "gusts of ill-temper" when his opinions were crossed. He was so expert and so exactingly knowledgeable in matters of literature that he bristled to the point of apoplexy when confronted by the slightest inaccuracy in connoisseurship or any lapse in taste.

In the evenings, he ritualistically read by candlelight. He dilated on this and expatiated on that in a shrill, metallic voice rendered still the more strange by certain peculiarities of elocution. For all this, visitors found him charming company and far from a garrulous old man. He was even known, on occasion, to give out with an expansive laugh.

In later years, Swinburne composed major studies of literary kingpins such as Byron, Blake, and Ben Jonson. Swinburne himself soon became the subject of studies, dedicatory poems, appreciations and commemorations of all sorts by fellow men of letters the august likes of Ezra Pound (who lionized him), fuddy-duddy T. S. Eliot (who, in some ways, denigrated him), Edmund Gosse, Edmund Wilson, Mario Praz, George Saintsbury, and C. M. Bowra. A. E. Housman wrote a précis on him. Thomas Hardy, who idolized Swinburne and never spoke of him "save in words of admiration and affection," penned a touching poem about him while sitting next to his grave, after placing a spray of ivy at the spot where he spends "the vast forever."

Swinburne's literary criticism has prompted a good deal of comment. It has been called "a tangled thicket of prejudices and predilections marred by exaggerated vituperation and praise, digressiveness, and a flamboyant style." Then again, "he was, of course, a master of the phrase, and it never happened that he touched a subject without illuminating it with some lightning-flash of genius, some vivid, penetrating suggestion that outflames its shadowy and confused environment." But "even his best appreciations are disfigured by error in taste and proportion" and "when aroused to literary indignation the avalanche of his invective sweeps before it judgment, taste and dignity. His dislikes have all the superlative violence of his affections" and are apt to spawn a glib melee of epithets and imprecations. Nonetheless, any characterization of the lordly literateur as some sort of quibbling crank is doomed to fall short of the mark, since consensus confirms his unshakeable place in the firmament of critical exegetics.

Swinburne's twilight years were dazzlingly prolific. Among his late works were Songs of the Springtides; Tristram of Lyonesse; Locrine; Astrophel and Other Poems; A Century of Roundels, dedicated to Christina Rossetti, Swinburne's favorite poetess after Sappho; and a number of essays and studies, such as those devoted to Hugo and Shakespeare. His physical aspect changed and he gradually grew deaf while contributing over two hundred reviews and poems to periodicals, and publishing twenty volumes of prose, poetry, and verse drama on historical and classical subjects. "He rose to an eminence as a learned man of letters and a poet on the old, grand scale, a master of his craft and the creator of a distinctive voice and presence." Installed in a suitable environment, and insulated from perturbations and vexations, Swinburne had shed the skin of his disorderly, self-destructive existence and emerged from the chrysalis as a new creature – the venerable man of letters. He had produced copious quantities of poetry and prose during his years of dangerous illness. Now that he was ensconced in feather-down confinement, his productivity was undiminished and his glory unsubdued. Watts-Dunton's decisive, humane gesture had preserved for posterity a poet who would continue to create for thirty years after the crisis.

FINAL SUMMONS

In April, 1909, after traipsing in the woods without a brolley or a cloak, Swinburne contracted influenza which flared into pneumonia. After a handful of delirious days and fever-fuddled nights during which he muttered incomprehensibilities in scrambled Greek, he succumbed at the age of seventy-two. He was exactly five feet in height and his shoe-size was 8 ½. He was buried on the Isle of Wight, near the family home at Bonchurch which, after his demise, became a convent. Queen Victoria declared she had heard him held to be the "finest poet in my dominions." He had been considered to hold the post of Poet Laureate following Tennyson but was rejected because he had once made a diplomatically reprehensible statement about the Russian Tzar. (He advocated tyrannicide.)

RANK AND STATURE

If consensus fixes Swinburne's artistic zenith at the period of Atalanta in Calydon and the first series of Poems and Ballads, the flower of later periods found him still singing "in chaste magnificence" and, while his stature rests securely on a handful of supreme masterpieces which alone are sufficient to ensure his immortality, his position as a critic of high distinction and his eminence as a general man of letters remain unshakeable. Lauded and denigrated both during his life and since, his mythical status, like Byron's, like Wilde's, firmly endures.

In 1911, Edmund Gosse, Swinburne's amanuensis, offered a fitting memorial tribute to the master with this stirring summation:

Of his poetic technique, it may safely be said to have revolutionized the whole system of metrical expression. It found English poetry bound in the bondage of the iambic; it left it reveling in the freedom of the choriambus, the dactyl and the anapest, entirely new effects; a richness of orchestration resembling the harmony of a band of many instruments; the thunder of the waves, and the lisp of leaves in the wind; these, and a score of other astonishing poetic developments were allied in his poetry to a mastery of language and an overwhelming impulse towards beauty of form and exquisiteness of imagination. In Tristram of Lyonesse the heroic couplet underwent a complete metamorphosis. No longer wedded to antithesis and a sharp caesura, it grew into a rich melodious measure, capable of an infinite variety of notes and harmonies, palpitating, intense. The service which Swinburne rendered to the English language as a vehicle for lyrical effect is simply incalculable. He revolutionized the entire scheme of English prosody. Nor was his singular vogue due only to his extraordinary metrical ingenuity. The effect of his artistic personality was in itself intoxicating, even delirious. He was the poet of youth insurgent against all the constraints of conventionality and custom.

No one did more to free English literature from the shackles of formalism; no one, among his contemporaries, pursued the poetic calling with so sincere and resplendent an allegiance to the claims of absolute and unadulterated poetry. Some English poets have turned preachers; others have been seduced by the attractions of philosophy; but Swinburne always remained an artist absorbed in a lyrical ecstasy, a singer and not a seer. His personality was, in its due perspective, among the most potent of his time; and as an artistic influence it will be pronounced both inspiring and beneficent. The magnificent freedom and lyrical resource which he introduced into the language will enlarge its borders and extend its sway so long as English poetry survives.

ENVOI

Swinburne's funerary enclosure bears no inscription from his vast literary annals. If it did, such an inscription might consist of these lines from his poem Nephilidia:

"Life is the lust of a lamp for the light that is dark till the dawn of the day when we die."

0 comments:

Post a Comment